pearls on a string

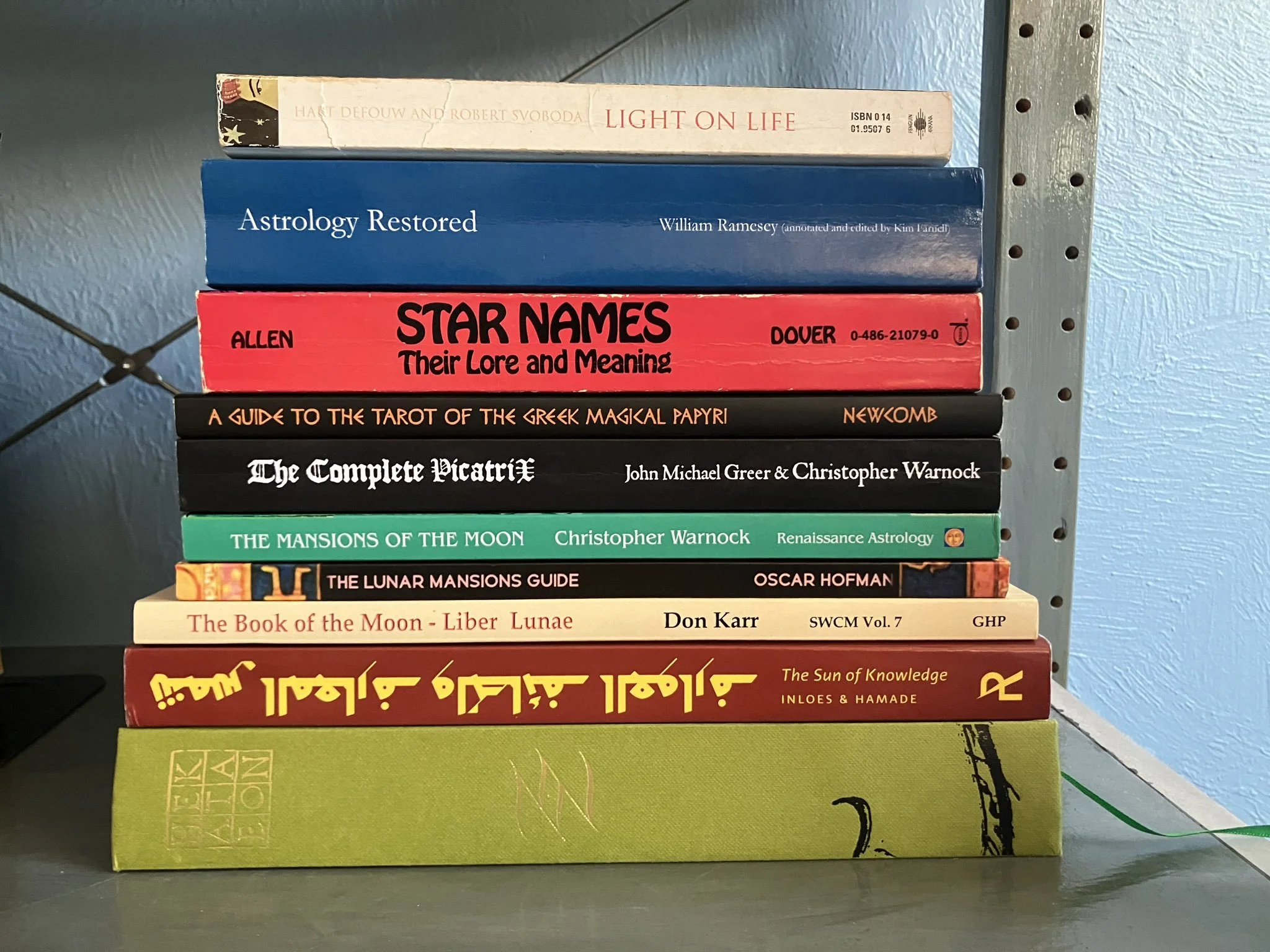

my favorite works on the lunar stations

a collection of ritual implements

The next part of the Station Stroll project I’d like to introduce is what I’m calling my annotated bibliography. I’m synthesizing the research I’ve done in various ancient texts, academic papers, and modern books for this project, and I’m excited to show you my list of sources. Many of them are likely familiar to you but I’ve also found quite a number of interesting gems. The questions of the origins of the lunar stations and their exact character have been extremely interesting to academics and the complexity of these answers is highly simplified in what is available for lay audiences. I’m excited to be a part of making connections between all of these threads.

I’ll share a link to the full bibliography so that you can read it yourself, but for this post I thought I’d pull out some of my favorite sources to show off. One thing before I start, though: fellow moon-nerds, have you read something intriguing that isn’t on my list?

To begin with, if I were just getting into the lunar stations for the first time, I would purchase two books: The Mansions of the Moon by Christopher Warnock, and The Sun of Knowledge by Ahmad al-Buni and translated by Amina Inloes and JM Hamade. The last things I want to share with you are 2 bonuses to get you going, both relatively short academic papers that need to be better known in our circles.

Best place to start

Christopher Warnock: The Mansions of the Moon: A Lunar Zodiac for Astrology and Magic

No discussion of the lunar mansions and their magic would be complete without highlighting Christopher Warnock’s work. Before most of us whippersnappers had cast our first astrology chart, Warnock was out here disseminating Latin texts and teaching courses on this ancient magic. We all owe him a tremendous debt of gratitude. Did you know that Warnock and Greer’s translation of the Picatrix, the first workable translation into English, was published in 2011? I have a copy of a first edition of The Mansions of the Moon with a 2010 copyright. It’s amazing to see how much work practitioner-researchers have been able to contribute in the last 14 years and much of it would not be possible without Warnock’s work.

The Mansions of the Moon is an ideal starting point for practitioners who don’t have much background in this area of study or kind of magic and want to get their feet wet right away. He walks you through the various ways of determining what station the Moon is in, the steps of preparing magical elections with the lunar mansion and making their talismans in the revived style of Picatrix, and gives his research and personal gnosis for each station. His collaborator, Nigel Jackson, shares his Picatrix-inspired ritual template for lunar station magic as well as a talismanic image he has prepared for each station, following the descriptions in Picatrix Book 4, Chapter 9. His book also contains a compilation of the key primary sources on the lunar stations that would have been familiar with our practitioner-ancestors in Latin-speaking Europe. If you get the 2nd edition, there’s even an ephemeris of the Moon’s position in each station through 2033 (the 1st edition only runs through 2018).

This book would be best for people who are especially motivated to practice lunar mansion magic. One slim volume (available in Kindle edition for 9.99 USD) and you’re ready to jump in. Considering my own temperament, it surely surprises no one that this book was the first place I started with my research with the lunar stations. I had made three talismans I loved before I ever purchased another book.

I believe my spirits drew me to my first copy, in fact. Right before I moved out of my hometown for good, I took one last trip to my favorite used bookstore. It wasn’t a very convenient time—the last thing I needed a week before moving hundreds of miles was another damn book! I just felt compelled to pay my last respects at the bookstore that had nurtured me since I was a kid and, there, I came across this bizarre-looking green book on astrological magic. In some ways, that was the first step on this long journey of initiation into the pattern of 28.

Most insightful

Ahmad Al-Buni: Shams al-Ma’arif • The Sun of Knowledge

Amina Inloes & JM Hamade translation and commentary: 2022

By “most insightful” here, I mean the most helpful source for my apprehension of the deeper history and nature of the stations.

Al-Buni was an Islamic philosopher in the 13th century, roughly contemporary with Picatrix. He wrote on mathematics and Sufism but the most influential part of his legacy was on magic and occultism. The Sun of Knowledge شمس المعارف was/is (in)famous in the Islamicate world as a grimoire of magic and sorcery. Though it is attributed to al-Buni, it is not clear that it was truly written by him in its entirety (I’ll leave it at that, though there’s a lot that could be looked into here if you’re curious).

Its reputation in the Arabic-speaking world is comparable to Picatrix in medieval Europe and it occupied a place in the folk imagination similar to the Necronomicon in contemporary American culture (which was based on Picatrix, among other things), its name almost synonymous with sorcery itself. Although the book has been burned and banned for centuries, it remains very well-known among Arabic-speakers and, I am told, it’s not difficult to find Turkish or Urdu editions in bookstores in their respective regions. Despite that, it has remained relatively unknown in the English speaking world and, as best as I can tell, Amina Inloes’ translation is the first translation of even a sizable portion into English.

The Sun of Knowledge is presented something like al-Buni’s own notes on this subject, not terribly well-organized by contemporary standards. It’s written in incredibly dense medieval Arabic that is rich with religious and cultural references. As someone with several years of Arabic study and very little Islamic education, I have found it completely impenetrable. Inloes suggests that preparing her translation was quite a feat and I believe her.

Revelore Press’ 2022 edition is a work of art, sumptuously illustrated by JM Hamade and presented in a way that makes this absolute unit accessible to an audience of contemporary practitioners who aren’t deeply familiar with 13th century Islamic thought. This edition is a selection of passages (chapters 1-8, 17 and 19 of the Arabic) reorganized into topical chapters rather than a full translation. It contains chapters on the occult nature of the Arabic alphabet, astrological elections, the lunar mansions, zodiac, fixed stars and planets, as well as an absolute smorgasbord of magical recipes. This grimoire is essential reading because it helps to situate the traditions of the lunar stations in their original cultural framework and opens up their complexity in a way that is impossible by reading only European texts.

I am no scholar of al-Buni, I’m just trying to keep my head above water in this deeply symbolic and complex work like the rest of you, but I think this work would be an excellent entry point to the Islamicate occult sciences for students of astrological magic. It contains nearly as much of Inloes and Hamade’s commentary as it does translation, which offers the reader plenty of support. Personally, I appreciate it because it situates this topic within Islamicate culture and the Arabic language, something that is not highlighted enough among current discussions about astrological magic. Astrological magic, as a whole, entered Europe through the Arabic-speaking world, and to erase that is to erase the greatest ancestors in the lineage of these traditions. You may not be a Muslim, you may not know any Arabic, but if you’re serious about learning about the stations, you must become familiar with their roots, none of which lie in Europe.

I’m sure I will be trying to break into al-Buni’s work for years to come and this edition has been an amazing starting point. For further research, my fellow Spanish-speakers should consider Jaime Coullet Cordero’s dissertation, a translation of what appears to be the entirety of the Shams al-Ma’arif into Spanish. The dissertation is well over 1000 pages long and I’ve only dug through it a little bit so make sure you report back to the rest of us if you uncover anything especially interesting!

Jaime Coullaut Cordero’s full translation with extensive commentary: 2009

As you get into al-Buni’s work, I highly recommend Daniel Martin Varisco’s commentary on the stations sections. It’s very helpful to open up that portion of the text.

Daniel Martin Varisco. 2017. “Illuminating the Lunar Mansions in Shams al-Ma’arif”

Most surprising

Abū ‘Alī Ibn Al-Hatim: De imaginibus caelestibus • On celestial images

Kristen Lippincott & David Pingree. 1987. “Ibn al-Ḥātim on the Talismans of the Lunar Mansions.”

The ghosts of Picatrix haunt every discussion on the stations, at least among English-speaking Westerners. There’s just no single text that has had more influence on the conversation about them, but I honestly find Picatrix very frustrating as a text. Though we now have excellent English translations of the Latin Picatrix that was so well-known in Europe, it doesn’t remove the fact that the quality of the translation into Latin left much to be desired in terms of scholarship. The Arabic Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm remains basically impossible to access in English. I’ll write a dedicated discussion of Picatrix later but, for now, I’ll focus on the two chapters that discuss the lunar stations: Book 1, Chapter 4, which contains a list of elections for each station, and Book 4, Chapter 9, which gives a talismanic recipe for each station. Picatrix 4:9 is essentially the foundation of the entire practice of lunar station magic as contemporary practitioners know it today, especially because it provides the names of the spirits who are in charge of each of the stations.

Did you know that that chapter isn’t even found in the original Arabic text?

That’s right—the text that everyone is referring to when they talk about making Picatrix-style talismans for the lunar stations was added in Medieval Spain. That chapter was originally written in Arabic, possibly several hundred years before the Ghāya, probably by someone named Abū ‘Alī ibn al-Hassan ibn al-Ḥātim. This person’s existence does not appear to be documented almost anywhere else and his background is completely undefined (except that he saw an eclipse in southern Europe on 19 July 939). The manuscript copy we have was clearly written in the hand of a 15th century scholar named Guglielmo Raimondo de Moncada, a Jewish convert to Christianity who was very familiar with Islam and Arabic. Guglielmo was fascinated by esoteric texts, in part because his father was a talisman-maker. This text was translated (poorly) into Latin (by someone else), and the heavily corrupted Latin version (attributed to a “Plinio” who some have interpreted to mean Pliny) was tucked into what would eventually become the Latin Picatrix.

In 1987, Kristen Lippincott & David Pingree produced a translation of the original Arabic into English, as well as a corrected Latin translation of the Arabic, which is the source I have linked for you here. The translators took care to transliterate the names of the rulers of each station as closely as possible to the original Arabic. If you look into it yourself, you will find that the names of these spirits in the Latin Picatrix are so badly corrupted that they are unrecognizable.

I bet that made the magicians’ ears all perk up! Go read this one!

Also check out Marc Oliveiras’ interesting paper that provides a Modern Spanish translation and a discussion of some proposed origins of the stations’ talismanic images (in Spanish).

Marc Oliveiras. 2009. “El de imaginibus caelestibus de Ibn al-Ḥātim.”

Most compelling historical account

Varisco, Daniel Martin. 1991. The Origin of the anwā’ in the Arab Tradition. Studia Islamica, 74, 5–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/1595894

This one is much drier than the others but so important for our ongoing conversations about the stations. Here, the author endeavors to present his take on the history and origins of the lunar stations in Arab culture. You’ll see all kinds of assertions brandished about out there about this system’s origin and many of them are based on shaky ground or questionable agendas. I personally find Varisco’s account the most compelling.

His essential thesis is that the systematize division of the ecliptic into 28 portions has its origins in Indian culture, but that the formal discourse and definition of it in Islamicate society was interpreted through Arab culture. More than just taking an Indian astrological system and replacing the Sanskrit names and lore with Arabic ones, the entire system itself was recreated in an Arab and Islamic form. The 28-fold lunar zodiac was essentially a skeleton borrowed from India and fleshed out in the Islamicate world by indigenous, pre-Islamic star lore. He suggests, among many other things, that the stations contain the whispers of pre-Islamic star cults focused around invoking the stars’ intercession to bring the seasonal rains.

He really gets into it! For more details, I’ll let you read it for yourself.

a pile of books dealing with the moon and lunar stations