an interlude on papyri and ancestors

on the greek (and egyptian) magical papyri

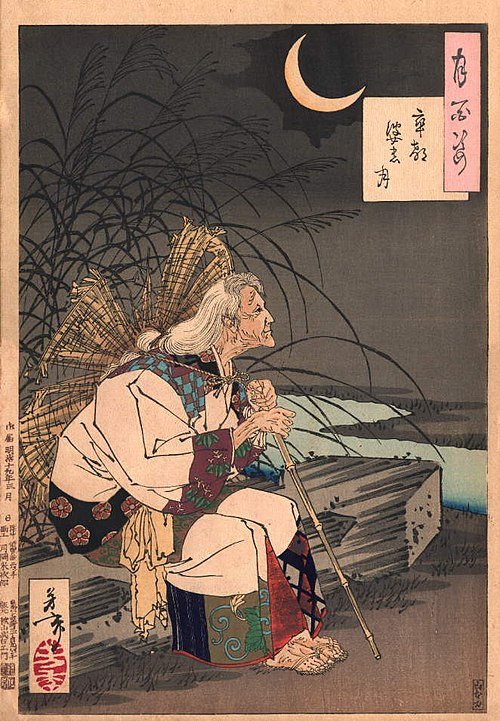

“Gravemarker Moon • 卒塔婆の月 Sotoba no tsuki” by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, from his 100 Aspects of the Moon collection of ukiyo-ē prints, via Wikipedia

This month we’re going to be taking a brief detour from discussing the lunar stations directly to talk about a tremendous source of lunar magic: the Greek (and Egyptian) Magical Papyri.

The stations as we use them today would not have had much if any penetration in Greco-Egyptian magic but I (and others) have taken advantage of some of these ritual techniques for working with the Moon and her stations.

These handbooks of Helleno-Kemetic magic are haunted with ambivalent spirits, far from angels of love and light. They can be spooky and sometimes a little gross—so I’ve decided to spend October sharing some of my thoughts on this curious corpus.

There will be three posts this month. The first will lay the groundwork for our conversation; the last two will detail the two spells I have drawn from to build my own lunar framing ritual. It is not directly an invocation of the lunar stations but it is the ritual I use to open each of my gnosis sessions, along with any other lunar magic I do. And don’t worry, station syncs will abound.

One of my goals with this work is to give an example of what the work of a practitioner-researcher might look like. I intend to center myself in an emic approach, an insider’s perspective on these practices.

In other words: I am not a classicist. I am a witch.

I investigate all the sources I have as thoroughly as I can and maintain the most rigorous citation practices that I can. Don’t mistake this attention to detail, though. I have no desire to make my research palatable for outsiders to these practices. Nowhere is it more true than my integration of Helleno-Kemetic magic into my lunar stations research, as I expect you’ll see as this all unfolds.

Again, all of this is ultimately in service of my station stroll, and that is what we will return to next month. For now, we’re going to take a detour into this dark forest of ancient papyri!

The “Greek” Magical Papyri

As I explained in my discussion of the role of gnosis to my station stroll, the entire practice began with performing a dream divination from the Greek Magical Papyri (abbreviated as PGM from here on out, standing for thier Latin name, Papyri Graecae Magicae) that I arrived at through Jason Augustus Newcomb’s PGM Tarot.

The PGM is a complicated corpus to dig into. It is, essentially, the collection of papyri that have been discovered since the 1800s which are written in either Greek or Demotic Egyptian and contain information about magic. These texts aren’t really a coherent “magical system” the way we might think of it today—they represent the highly syncretic cultural milieu of the magical scene in Upper Egypt. In many ways they’re more Egyptian than they are Greek, but they were written in (mostly) Greek so the Greek part of the corpus’s name stuck. They could perhaps best be called Greco-Egyptian. Another term you may see used to describe this cultural space is Helleno-Kemetic (from an anglicized version of the Greek word for “Greece” and the Egyptian word for “Egypt”) which I also quite like.[1]

They were never intended to be presented together and represent as many different perspectives as they have authors. Most of them were discovered more or less randomly in the antiquities market, and the origins of many of them are basically unknown due to the general ransacking of Egyptian archaeological sites. When they were grouped together and published, they were numbered arbitrarily (as far as I know, someone correct me in the comments) and those are the identifiers we use to describe them today.

As far as I know, PGM IV (3270+ lines long) and PGM VII (1025+ lines long) are the longest of the magical papyri we have access to today. My first spell for this framing rite comes from the papyrus we call PGM IV, which just means the fourth papyrus in the original collection. The citation for this first spell specifically is PGM IV 2622 - 2702: the fourth papyrus in the collection, lines 2622 through 2702. PGM IV sometimes known as The Great Papyrus of Paris or le Grande Papyrus Magique (because it is currently kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France) is the longest and most extensive of all of the magical handbooks preserved from antiquity. It has been extensively studied and it was among the first of the magical papyri to be translated into a modern language. Due to its length and lineage, many of the PGM rites that are most well-known to practitioners today come from this papyrus [2], and it seems to be equally popular among researchers. [3]

If you’re new to the PGM or Greco-Egyptian magic in general, PGM IV is a wonderful place to focus your attention.

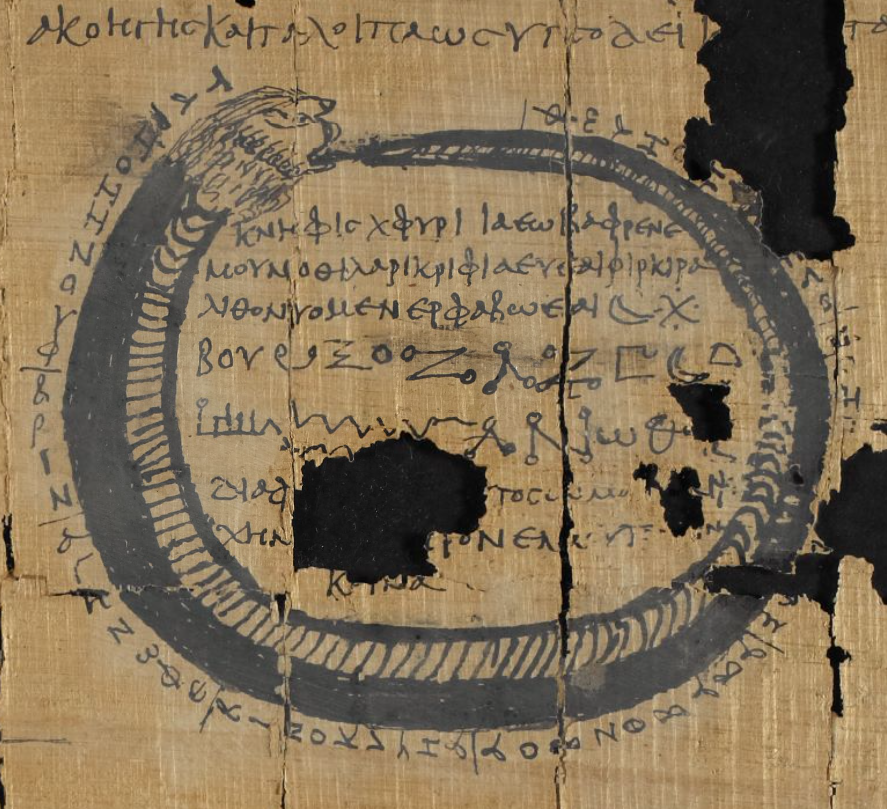

The second ritual I have drawn from is from PGM VII 756-94. Like most famous papyri, PGM VII has several names (while the text itself is unnamed and anonymous). It seems like the most common name is the one given to it by the British Museum: P.Lond. I 121, or just Papyrus 121 for short. This papyrus has been housed in the British Museum since it was discovered by E.A. Wallis Budge. I don’t fully understand the history of each of the papyri in the corpus but in a way it kind of doesn’t matter because their process of being “brought out of Egypt” (as it is often termed in older Egyptological work) was quite sketchy. Like PGM IV, PGM VII has been quite popular with researchers and practitioners alike. In particular it contains the very famous Ouroboros phylactery, depicted below. [4]

For more about the history and contents of PGM IV and VII, I recommend the work of Dr. Kirsten D. Dzwiza, who produced a long and fascinating open-access video about each of these papyri: PGM IV and PGM VII

The Ouroboros Phylactery from PGM VII, a classic Helleno-Kemetic charm

On the lineage of the papyri

The vast majority of the papyri were brought to Europe by someone who ran a huge racket in antiquities named Giovanni d’Anastasi. He is often described as a diplomat, adventurer, or merchant, but essentially he made a fortune “discovering” Egyptian antiquities and bringing them to Europe to be auctioned off to museums.

Have you ever wondered why all of this Greco-Egyptian business is housed in the British Museum in London or the Louvre and the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, rather than Alexandria or Luxor, where they’re from?

Yeah.

Budge, the acquirer of PGM VII, looks a tad better in the light of the historical record, but there’s no way to get around the fact that all of these collections were built from questionable-at-best transactions and grave robbery. There was a fortune to be had in pillaged antiquities during the Egyptomania of the 1800s.

The bulk of the collection traces its lineage through d’Anastasi and usually ends there since d’Anastasi kept the origin of all of these treasures a secret. Sometimes the PGM are called the Anastasi Handbooks because of this, but to me it seems strange to name this corpus after their manufactured historical dead end. Betz, the first translator of the PGM in to English, believes that at least the d’Anastasi portion was found in Thebes all together, the product of some other collector perhaps 1000 years earlier and found either in a grave or a temple library. [5]

Another name for the PGM is the Theban Magical Library or the Theban Cache, named for this first collector and, to me, it seems like a much more suiting name. Betz speculates that the Theban Collector was a magician himself and collected these texts for personal use, but that his attention to archival detail suggests that he was a scholar and a bibliophile. Magical texts like these were everywhere at one point in history but they were systematically destroyed and suppressed during the rise of Christianity so the reason we have such a magnificent cache of texts all from the same vague time period is because they were preserved before the book burnings, then “found” during the antiquities craze (that’s how I follow the story at least).

If this is true, then we must thank the life’s work of a single nameless Theban magician-ancestor who collected these texts and identified their value. If it weren’t for their systematic work and attention to archival detail, these papyri would have been burnt on a pyre by zealots or eroded to dust by the elements. It’s a powerful representation of the way the way a single life can impact the course of history. These texts span a range of several hundred years—a thousand years ago they would have already been the work of the ancestors for our Theban librarian-priest.

Speaking the lineage of these texts is an act of ancestral veneration.

Additionally, there is a lot that can be said negatively about the work of the colonial antiquities industry, but having these texts in their present form was the product of a long chain of scholars starting as soon as they showed up in the European libraries working up until today. There are still many discoveries being made about the Theban Magical Library and much more left to discover, even after a century of work.

That’s all for my teaser on the Theban Cache and its ancestors. Next time I’m going to tell you about a very interesting and weird spell that has become foundational to my practice, especially lunar work and dream divination.

Notes

[1] I adopted the term from sublunar.space, whose blog has been extremely influential on my engagement with the PGM, especially A Path of Helleno-Kemetic Magic.

[2] See the Consecration for All Things, which has been researched and discussed at great length by Alison Chicosky as well as the spell for picking a plant and the Egyptian rite for gathering herbs, not to mention the Mithras Liturgy, one of the most thoroughly researched rites in all the PGM.

[3] There was an entire conference focused solely on this papyrus in 2022 that I’m sad to have missed. The program seems very enticing! I hope to look into the work of these researchers more in the future.

[4] For example, see this write up on a dream magic spell or the ritual for meeting with your personal daimon. While I was working on this essay, my friend Sadalsuud found this thread on X detailing the similarities between a spell from this papyrus that eerily resembles a very similar Chinese spell.

And, as far as the Ouroboros phylactery, it has been extensively researched by Alison Chicosky, who often produces them for sale on her website and has taught workshops on the production of this phylactery. Aside from the papyrus, it has also shown up in magic gems from late antiquity. Enticing!!

[5] Basically all of this comes out of the introduction to Betz and d’Anastasi and Budge’s Wikipedia pages + my opinions